Well-being approached through capacity happens in the vanguard of the other beginning, a metaphysics for reality's potential. Agamben helps understand the experience of this register, of human freedom grounded in the privative capacity to withhold, to choose not to (be or do). This privation is experienced through the facticity of existence, the site where the withdrawal of disclosure may be apprehended. Agamben suggests that the experience that most fully represents the complexity of radical incapacity (the capacity for death, finitude), the freedom that follows paradoxically from absolute powerlessness, is love (passion). On one hand passion motivates action, the mood of wanting and being able, and on the other the loss of control or mastery. In love (passion) one undergoes an event of pure receptivity that distinguishes capacity from its peer faculties of reason (knowledge) and will (intention).

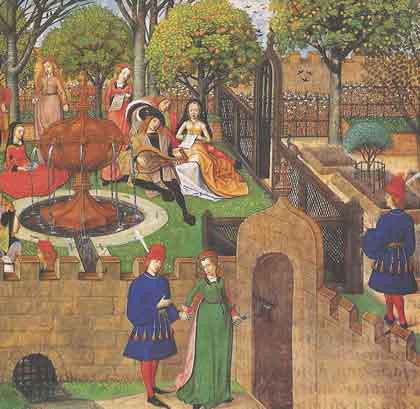

The crucial lesson for apparatus invention in Agamben's account is that the issue is not Erlebnis (immediate lived experience) but Erfahrung (living reiterated in the fold of language). The lesson is not in corporeal sexuality but in the Troubadour invention of a paradigmatic relationship, a scenario of courtly convention, the Dark Lady and the poet desiring what is not attainable. Based on a detailed review of Medieval medical theories (sensation becoming phantasm in imagination), Agamben uses this invention to explain how the imagination (the faculty augmented in electracy) functions. The insight of the invention is that poetry creates an opening in facticity, a third space, mapping precisely the event of contact between inner experience and external environment. This contact triggers epiphany (revelation). The structure is the same as that of chora, mediating between Being and Becoming, with poetry supplying the choral dimension. Part of the lesson has to do with happiness, figured in the complexity of the troubadour joi d'amour (that Nietzsche also endorsed as the Gay Science), fixing desire on the unattainable. The argument is that desire is only satisfied by means of the intervention of imagination, realized through language.

Agamben generalizes the Troubadour historical invention of courtly love to a new model of invention or creativity, that is to electrate logic what Aristotle's topics is to literacy. Language as practice has two fundamental capabilities (two modes of exhibition): saying, and showing. Literacy covered saying. Aristotle's metaphysics developed an isotopy coordinating Euclidean space, logical dialectics (opposition) in language, and reasoning (thinking). Electracy shifts to the dimension of showing (indication, gesture, augmented in digital imaging). Agamben outlines the isotopy articulated for this register: topology (labyrinth) as space, fetish emblematics as logic, and passion (love) as psychology. The register of showing does not replace saying, but develops this faculty to supplement those already institutionalized in the historical apparati. Modernism adopted as the sources or authorities for its innovations in this capacity the productions of children, "savages," the insane (perverts Agamben would say), and poets. Agamben clarifies what must be learned from these sources, who explore the capacity of language to support a dimension of the un/real --the un/attainable.

See Giorgio Agamben, Stanzas: Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, University of Minnesota, 1993.