Watermark (Joseph Brodsky)

We are reverse-engineering a "Republic" for electracy, first identifying the poetics of Plato's version, and then proposing an allegory of our own. We continue to work within the frame of literacy for now, using heuretics to imagine a work native to electracy that models the education we already are performing. A basic device of Philosophy is to create a "conceptual persona," a person in a situation, to dramatize how to live according to the speculative theory. "Socrates" is the conceptual persona created by Plato, based on the historical figure of his mentor, whose historical life was appropriated and fictionalized to represent the world view being invented in the Academy. Our candidate for an electrate conceptual persona could be any artist, in principle (such as Jana Sterbak), but given our allegory the ideal figure is Joseph Brodsky. As was the case with Socrates, the persona is not a figure simply to observe, but to emulate. The practices of literacy or of electracy are for everyone, and we study the persona to learn how to generalize his or her conduct into a practice of education. It will not be a written dialogue defining the properties of an ideal city, however, demonstrating along the way a particular form of argumentation and logic, as in the case of the Republic.

How will we encounter our paragon in an electrate way? Plato's purpose was not necessarily to have his students learn to write dialogues (although some did), but to learn dialectic (the new logic made possible by alphabetic writing). The equivalent of the dialogue interface that brought students into relation with "Socrates" for us is a filmic treatment of Joseph Brodsky in Venice, perhaps a screenplay adaptation of Watermark, the lyric prose autobiographical portrait Brodsky wrote in the latter part of his life. Brodsky was born (1940) and raised in Leningrad, later St Petersburg. In 1964 his poetry got him convicted of "social parasitism," and sentenced to five years in a labor camp. In 1972 he was exiled permanently. It is appropriate in our context to pick up the transformation from literacy to electracy with an exiled poet, considering Plato's exclusion of poets from his city. It is ironic, also, that Socrates was executed by Athens for "corrupting the youth."

Once settled in the United States, where he found work teaching, Brodsky visited Venice nearly every year, going in the month of December, the winter, time of high water. He went there simply "to be" for a time, and (if fortunate) to write a few poems. "And I vowed to myself that should I ever get out of my empire, should this eel ever escape the Baltic, the first thing I would do would be to come to Venice, rent a room on the ground floor of some palazzo so that the waves raised by passing boats would splash against my window, write a couple of elegies while extinguishing my cigarettes on the damp stony floor, cough and drink, and, when the money got short, instead of boarding a train, buy myself a little Browning and blow my brains out on the spot, unable to die in Venice of natural causes" (41). The tone and sentiment at once express the romance and irony of his state of mind. The relevance of this particular work for us is that it is not poetry, but the life of the poet, that is put forward (albeit manifesting the craft of great poetry).

Why Venice? He reported a childhood memory of receiving a gift of a copper gondola, brought back by his father from a trip to China. He dreamed of traveling to Venice as a child. In exile, the resemblance between the cities--their geographical situation in marshland, the presence of canals--made Venice a place of "rememoration." Rememoration, or "arbitrage," is a condition in which the object itself is not remembered, but the memory of it, applied when the place or thing remembered is a composite (Boym, 303). This composite memory is fostered in mystory (the electrate genre we will be practicing), to access not only the GPS of our physical navigation, but also the EPS or existential positioning system of our wayfinding. It is worth sketching in Brodsky's mystory briefly, to note the four levels of our allegory (countering the four levels of Plato's analogy of the line). This gift of the gondola represents the Family story. The importance of the gondola is indicated by the fact that it was one of the items present on the bookshelf, documented in the photograph taken of his room the day Brodsky went into exile. For Community history a good candidate is the Soviet Sputnik program, building up to sending men into space by putting dogs into orbit. Brodsky used these dogs shot into space as a metaphor for what it is like to live in exile (your capsule is your language, and soon you realize that the trajectory is not back to earth, but out into outer space).

As for mythology (entertainment narrative), Brodsky himself describes the relevant work, a novel (a series of three novels in fact) by Henri de Régnier, published in the later 1930s, with one entitled "Provincial Entertainments," set in Venice in the Winter. He read these books, characterized as picaresque detective stories, with the usual plot of love and betrayal, in his early twenties. They were not great literature, but he learned from them that what makes a good narrative is "what follows what." For some reason, he adds, he came to associate this sequence with Venice (38). He leaves unspoken his own experience of a broken heart, a betrayed by his beloved with his best friend. The point for now is to note how Brodsky imagines his experience through the frame of a certain kind of B movie, even classifying its genre as "melodrama," with the overtones that this classification carries for us.

The scene includes a Proustian involuntary memory, triggered by a smell that Brodsky identified as that of frozen seaweed, reminding him of his childhood home on the Baltic, and despite admitting that his childhood was not happy, the sensation at that moment gave him a feeling of utter happiness (the happiness experienced biting into a tea biscuit started Proust on his search for lost time). In any case, Brodsky on his first visit to Venice imagined himself in an adventure narrative. "So I lifted my bags and stepped outside. In the unlikely event that someone's eye followed my white London Fog and dark brown Borsalino, they should have cut a familiar silhouette. The night itself, to be sure, would have had no difficulty absorbing it. Mimicry, I believe, is high on the list of every traveler, and the Italy I had in mind at the moment was a fusion of black-and-white movies of the fifties and the equally monochrome medium of my métier. Winter thus was my season; the only thing I lacked, I thought, to look like a local rake or [carbonaro] was a scarf. Other than that, I felt inconspicuous and fit to merge into the background or fill the frame of a low-budget whodunit or, more likely, melodrama" (4).

Share this

Comments

Analogos

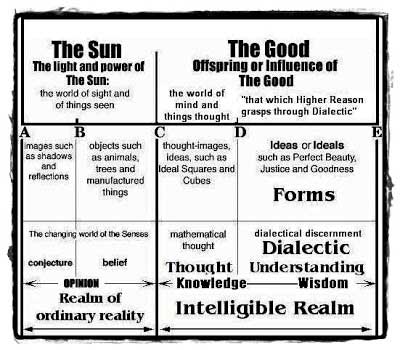

Plato makes explicit the structure organizing his allegory of the cave by supplementing it with the "analogy of the divided line." The figure in the allegory--the distinction between the condition of the cave and that of the great outdoors--uses experience of the sensory sensible perceptible world to show the difference between ignorance and knowledge in the intelligible conceptual world of ideas. The rhetorical figure is hypotyposis, proportional analogy--A is to B as C is to D. The eye-sun relationship is in perception what the soul-good relationship is in thought. This ratio underlies "Justice" in Greek metaphysics: understanding ratio, proportion, as the rule of order, constitutes reason. The explanation in the dialogue indicates the point of departure for our reoccupation of the Republic, moving into the old dwelling and remodeling it with a new metaphysics. "Now take a line which has been cut into two unequal parts, and divide each of them again in the same proportion, and suppose the two main divisions to answer, one to the visible and the other to the intelligible, and then compare the subdivisions in respect of their clearness and want of clearness, and you will find that the first section in the sphere of the visible consists of images. And by images I mean, in the first place, shadows, and in the second place, reflections in water and in solid, smooth and polished bodies and the like," writes Plato. This realm of images is the lowest of the four levels of the line, representing conjecture only. The upper half of the visibility consists of physical things themselves, representing belief (opinion, doxa). The intelligible invisible realm relates knowledge, especially knowledge of mathematics, to the highest level of intelligence which is understanding of Ideas recording truth, grounded in the Good as first principle.

The electrate allegory also includes four levels (the popcycle, discovered through the practice of mystory, whose nature we are encountering), but without the dualism or hierarchy of reality asserted in Plato's metaphysics. "No ideas but in things," a poet wrote, and that is what we find in Watermark: a metaphysics of immanence, an engagement with the material perceptible city of Venice. A few citations indicate the association of Brodsky's experience with the lowest realm of reflection. The poet confirms the power of sunlight and shadow constituting the visible half of Plato's ratio, but then remains within it to articulate further tropes.

"The upright lace of Venetian facades is the best line time-alias-water has left on terra firma anywhere. Plus, there is no doubt a correspondence between--if not an outright dependence on--the rectangular nature of that lace's displays---i.e., local buildings--and the anarchy of water that spurns the notion of shape. It is as though space, cognizant here more than anyplace else of its inferiority to time, answers it with the only property time doesn't possess: with beauty. And that's why water takes this answer, twists it, wallops and shreds it, but ultimately carries it by and large intact off into the Adriatic" (43-44).

"Should the world be designated a genre, its main stylistic device would no doubt be water. If that doesn't happen, it is either because the Almighty, too, doesn't seem to have much in the way of alternatives, or because a thought itself possesses a water pattern. So does one's handwriting; so do one's emotions; so does blood. Reflection is the property of liquid substances, and even on a rainy day one can always prove the superiority of one's fidelity to that of glass by positioning oneself behind it. This city takes one's breath away in every weather, the variety of which, at any rate, is somewhat limited. And if we are indeed partly synonymous with water, which is fully synonymous with time, then one's sentiment toward this place improves the future, contributes to that Adriatic or Atlantic of time which stores our reflections for when we are long gone. Out of them, as out of frayed sepia pictures, time will perhaps be able to fashion, in a collage-like manner, a version of the future better than it would be without them. This way one is a Venetian by definition, because out there, in its equivalent of the Adriatic or Atlantic or Baltic, time-alias-water crochets or weaves our reflections---alias love for this place---into unrepeatable patterns, much like the withered old women dressed in black all over this littoral's islands, forever absorbed in their eye-wrecking lacework. Admittedly, they go blind or mad before they reach the age of fifty, but then they get replaced by their daughters and nieces. Among fishermen's wives, the Parcae never have to advertise for an opening" (124).