The Conflict of Institutions

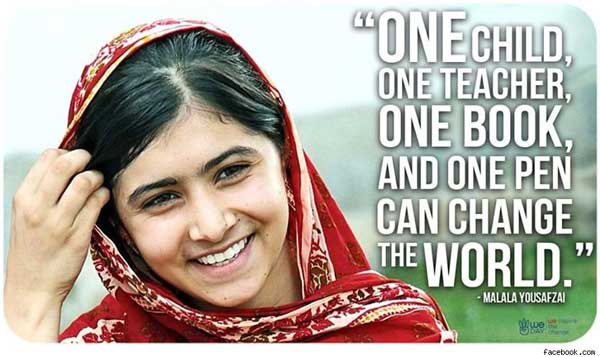

Shall we speak of education proper? The one organized in the institution of School, by means of books, reading and writing, literacy, the knowledge that evolved into science? Citizens of some societies take this institution for granted, although it is of recent date. What if attending school put your life at risk? News of a certain confrontation reached me through global media, in the comfort of my study. Here is Malala's own account of the event.

"When our bus was called that afternoon, the other girls all covered their heads before emerging from the door and climbing into the white Toyota van with benches in the back.

I sat with my friend Moniba and a girl called Shazia Ramzan, holding our exam folders to our chests and with our school bags under our feet.

The bus turned right off the main road at the army checkpoint as always and rounded the corner past the deserted cricket ground.

I don’t remember any more. But I now know that a young bearded man stepped into the road and waved the van down. As he spoke to the driver another young man approached the back.

“Who is Malala?” he demanded. No one said anything but several of the girls looked at me.

I was the only girl with my face not covered. He lifted up a black pistol, a Colt .45. Some of the girls screamed and Moniba tells me I squeezed her hand.

The man fired three shots. The first went through my left eye socket and out under my left shoulder. I slumped forward on to Moniba, blood coming from my left ear, so the other bullets hit those near to me.

One went into Shazia’s left hand. The third went through her left shoulder and into the upper right arm of another girl, Kainat Riaz.

My friends later told me the gunman’s hand was shaking as he fired. By the time we got to the hospital my long hair and Moniba’s lap were full of blood. I was rushed to the intensive care unit of the Combined Military Hospital, Peshawar."

A Taliban commander, Adnan Rasheed, in an open letter addressed to Malala, defended the attack by explaining that the problem was not education as such, but which kind, which institution. It was true that Pakistani Taliban had blown up hundreds of schools in the SWAT region, but these were schools teaching "a satanic or secular curriculum." Rasheed's advice and appeal to Malala was to return to Pakistan and enroll in an Islamic school for women. "Use your pen for Islam," he wrote, "and plight of Muslim ummah (community) and reveal the conspiracy of tiny elite who want to enslave the whole humanity for their evil agendas in the name of a new world order." (Associated Press, July 18, 2013).

Here is fundamental division, cutting across any individual popcycle: that between the two apparatuses (apparati) -- orality and literacy, Religion and Science, Church and School. It is important to understand the drama of Rasheed and Yousafzai in this historical context, as representatives of these two orders. The differences are metaphysical, referring to the set-up of reality itself. A glimpse of optimism may be available in the fact that the two parties are from the same culture and society, language and region, with the difference being rather gender, a man and woman. Hollywood knows how to tell that story: Rasheed and Yousafzai meet at an international United Nations conference and fall in love.

Share this

Comments

Terror

Why does learning provoke violence? Before Malala and the Taliban there was the fatwa issued by Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran in February, 1989, calling for the death of Salman Rushdie, the Indian British author of The Satanic Verses, a novel that was accused of blaspheming Islam. The metaphysics of electracy is invented out of aesthetic judgment, the capability of imagination, as distinct from the virtues of scientific and ethical judgment. Salman Rushdie's encomium for Gabriel Garcia Marquez, on the occasion of the latter's passing, shows the promise of the arts as a scene of global community. "When I first read Garcia Marquez I had never been to any Central or South American country. Yet in his pages I found a reality I knew well from my own experience in India and Pakistan. In both places there was and is a conflict between the city and the village, and there are similarly profound gulfs between rich and poor, powerful and powerless, the great and the small. Both are places with a strong colonial history, and in both places religion is of great importance and God is alive, and so, unfortunately, are the godly" (New York Times Book Review, May 18, 2014: 26). It is this kind of analogy, finding the equivalent in one's own place, that is fundamental for electrate community.

That cosmopolitan attitude is not universally embraced. A jihadist murdered the filmmaker Theo Van Gogh, a relative of the artist Vincent Van Gogh, for making a film depicting the abuse of women in Muslim communities. The pattern continues in the violence provoked by the publication in newspapers of cartoon caricatures of the Prophent Mohammed. Freedom of the press or of expression, a primary value of secular society, conflicts with principles condemning blasphemy in religious culture. That the primary issue concerns the status and rights of women is evident in the continuing atrocities committed by the Nigerian radical jihadist organization known as boko haram (the phrase means roughly "western education is a sin"). Taking credit for burning schools and massacring children, the group recently abducted over 300 school girls aged 16-18, in order to sell them into various conditions of slavery.

We are still within this historical process of secularization, the separation of science from religion (the dissociation of apparati), a progression whose prototype was the execution of Socrates by the City State of Athens (by democratic vote). The equally famous case is that of Galileo, forbidden by the Catholic authorities from publishing his work supporting heliocentric cosmology, on pain of torture and death -- a history given definitive form in the play by Bertolt Brecht. And lest we think that the violence cuts only one way, we should remember that the age of revolution born of the Enlightenment, unleashed much destruction and murder aimed at the Church as institution of oppression. Both the French and Soviet revolutions, in the name of enlightenment against superstition and corruption, attempted to suppress religion as enemy of the people. Both also resulted in their respective versions of a reign of terror. Here is a name for a byproduct of apparatus adjustment: terror.

Metaphysical Twerk

How does this history of terror appear from the framing (the set-up, the apparatus) of electracy? History shows the pattern, providing the analogy to understand what is happening today. The nation state eventually separated from the church (the Holy Roman Empire, for we are speaking of the Western tradition), and science separated from religion, by forming its own societies and institutions. Similarly, in electracy, the capitalist corporation is separating from the nation state, and entertainment is becoming an autonomous global popular culture. This most recent version of the shifting of historical "tectonic plates" is documented in Benjamin R. Barber, Jihad Vs. McWorld: How Globalism and Tribalism are Reshaping the World. His title reminds us of the three orders of apparatus creation: communications technology, institutional practices, identity formation (individual and collective). Tribe and Spirit (soul) are to orality what State and Self are to literacy. The apparatus analogy tells us that these givens are undergoing transformation again.

Barber's point is that what instigated the contemporary conditions of terrorism is not church vs. state, tribe vs. nation, but (as the title says), Jihad vs. McWorld. The trigger is the emerging force of the capitalist corporation and its manifestation as global entertainment, fronting an enormous jingle of consumerism. An electrate set-up does not replace that of the established apparati (right vs wrong in orality; true vs. false in literacy), but takes up its own metaphysics, addressing the capacity of the human body for pleasure-pain, attraction-repulsion: jouissance (to use the French term). Well-being, individual thriving against suffering, this is the purpose and commitment of electrate metaphysics.

We will discuss in more detail elsewhere the specifics of electracy, but for now we can identify the analogy: the Athens of electracy is nineteenth-century Paris, Montmartre specifically; its Academy is the cabaret scene of bohemian Paris (Le Chat Noir, for example, beginning in the 1880s), culminating in Zurich, the Cabaret Voltaire, during World War I. What topical logics are to literacy (codified by Aristotle, Plato's student and founder of his own academy, the Lyceum), dadaism and the bachelor machine are to electracy. The cabaret venues from Montmartre to Zurich and beyond continue in the casinos of Las Vegas today, but their true heirs circulate globally in American popular culture. Entertainment is a metaphysics, an institutional grounding for the electrate apparatus, dubbed McWorld, to alert us to its own manner of violence.

The nation state (Barber argues) is beset on both sides by Jihad and McWorld. What the Taliban fear is not so much Malala becoming a medical doctor (which is her ambition), for there are plenty of women with M.D.'s in Pakistan, but that she will go to Vegas and learn to twerk.

The right to learn

Electrate learning is configured in a specific way. We said it is self-addressed, and its motivation is an experience of justice, or rather, of injustice. There is a disturbance in the world (in the force, as one of our mythologies has it). You experience it, recognize it. No one has to explain it to you at this level. It addresses you, which is what the Ancients said about beauty. It is radiant, it appears, it is manifest, not hidden. It impinges upon your attention. The prototype for us, consultants for the EmerAgency, is the attempted assassination of Malala. This act was unjust, not right, a symptom of chaos, disorder. But there is much more to understand and invent with respect to justice. If not that act then some other one touches you. Select that event and appropriate it for your archive of learning.

We may take as a point of departure, as a declaration of purpose, the address Malala gave before the United Nations:

So here I stand... one girl among many.

I speak – not for myself, but for all girls and boys.

I raise up my voice – not so that I can shout, but so that those without a voice can be heard.

Those who have fought for their rights:

Their right to live in peace.

Their right to be treated with dignity.

Their right to equality of opportunity.

Their right to be educated.

Her appeal raises a framing question for the global society emerging within electracy. Malala's demand for rights resonates with that of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri in Empire: "Rather than global security, then, what is proposed here is a global constitutionalism, or really this amounts to a project of overcoming state mperatives by constituting a global civil society. These slogans are meant to evoke the values of globalism that would infuse the new international order, or really the new transnational demcoracy" (7). The imperative is not new. The analysts point out that for rights to be valid, there must be some entity with responsiblity that recognizes them. Hence the Hardt & Negri proposal of a global civil society. Let this challenge constitute a platform for electrate education.