Apparatus (Context #1)

This Group (and subsequent ones) hosts a conversation exploring the implications of electracy (apparatus theory) for education in a civilization adapting to digital technologies. The conversation is first person, the posts are signed, offering my own acccount of how I encountered this question. There is no attempt to be prescriptive or make normative claims. Rather, each contributor to the conversation (whether here or in some other venue) explains how change looks from his or her vantage point.

In my case, I came to questions of education reform through comparative literature, critical theory, media studies, as a teacher of Humanities General Education courses, Argumentative Writing, History of Criticism, Film Studies, Networked Leraning. I first encountered "grammatology" (the history and theory of writing) in graduate school (1970), reading Jacques Derrida's Of Grammatology in the context of writing a dissertation on Rousseau. "Grammatology" resonated with my first encounter with Marshall McLuhan's Gutenberg Galaxy as an undergraduate (1966). Adopting grammatology as a disciplinary guide after graduate school led to the work of such scholars as Walter Ong, Eric Havelock, and Jack Goody, among others. The Toronto School provided some ballast for the more radical work of French theory, the Tel Quel school, with which Derrida and many other post/structuralists were affiliated. The concept of apparatus (dispositif)--which came to organize my own inquiry-- was developed by Tel Quel theorists, who also were transforming the concepts of text, and of writing itself (écriture). Reading this scholarship and theory in the context of teaching introduction to argumentative writing in the morning, and film studies in the afternoon, produced the insight that "film" (multimedia recording) is the "text" of our civilization, with all the implications not just of equipment change, but civilizational shift. I introduced the term "electracy" ("electricity" + "trace," the latter invoking one of Derrida's keywords), to clarify that inquiry about new technologies of information and communication concern the whole social machine. The following statement (cited from one of my blogs) is how I formulate our question.

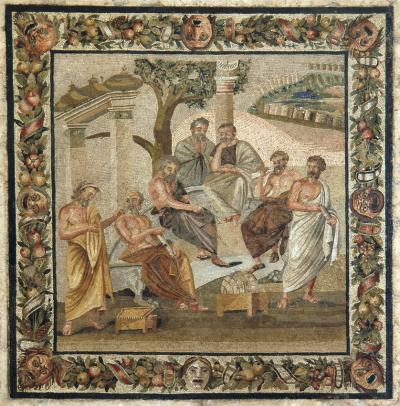

Electracy, like literacy and orality before it, is an apparatus, meaning that it is a social machine (part technological, part ideological, part metaphysical). An analogy with the invention of literacy guides our experimental approach to electracy. The Classical Greeks invented alphabetic writing (the vowel, signs recording the spoken word, the material support for inscription); school and its practices (the Academy, the Lyceum, in which were invented the categories, method, concept, logic — in short: science); individual and collective identity behaviors (selfhood, democratic state).

The question pursued here is: what are the electrate equivalents of the literate institutional practices and identity formations? Despite all the explicit statements made by leading commentators rejecting technological determinism, much of the best theorizing of new media and digital technology in general today neglects the insights of “apparatus”: that the Internet is an emerging institution that is to electracy what school was to literacy; that the categorial, logical, and rhetorical practices needed to function natively in this institution have to be invented, and moreover that the invention of an image metaphysics (the equivalent of what Aristotle accomplished for the written word) has its own invention stream, independent of the features of modern recording equipment.

Share this

Comments

Boundary object

"Education" is a "boundary object," meaning that it is shared among many interested parties, including every discipline and profession found in the university. There is some consensus that the dispersal of knowledge in the proliferation of disciplinary specializations, each separated from the other in an array of isolated "silos," is motivated not by the nature of knowledge itself, but reflects the limitations of literacy as an apparatus. Furthermore, it is apparent that this institutional configuration is no longer desirable or sustainable. The question of reform opens within this context, but the way forward is not obvious, and here consensus ends. Meanwhile, the university is migrating its assets and resources online: digitizing its archives, establishing online curricula, computerizing administration. It has no choice. Information is expanding at such a pace that the print medium with its libraries for storage and retrieval is overwhelmed.

Historically this seemingly basic shift from print storage and retrieval to data base support repeats an initial stage of previous transformations. McLuhan famously observed that the content of the new medium is the old medium. The Classical Greeks wrote down their epics and related matters of oral culture. The unforeseen consequence over several hundred years was the discovery of patterns in language not noticed in orality, but manifested in the visual graphic display of writing. This pattern finally was codified in Plato's Academy--the first school--as the structure of "concept," from which followed all the powers of literate metaphysics, including ultimately modern science. The transition from manuscript into print manifests a similar pattern, while continuing the fundamental worldview of literacy. The first step again was to put into the new medium of print the major documents of the civilization--in this case the Bible--with unforeseen consequences, associated with the Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation, secularization, the nation state. Not that print is "cause" in some deterministic way, but that innovations in technology of communication provide access to workings of the larger matrix of the social machine that is the apparatus, involving invention of forms and practices of institutions, and of identity behaviors individual and collective.

The historical analogy mapped onto electracy suggests that something similar is happening today, meaning that the most basic adaptation of modern society to new media--currently the digitizing of the entire cultural archive--provides the basis for all subsequent metamorphosis of civilization. Two features at least are evident in the analogy: 1) That the new metaphysics (operating system) of electracy has to be (and is being) invented and is not determined in advance, but that the inventions exist already in the potential mapping between the content of the archive (the cumulative production of literate civilization) and digital technology. 2) Every primary dimension of electracy--technology, institutionalization, individual and collective identity--will be other than those formations organizing literacy (and orality). History in this sense simply confirms the first rule of innovation (creativity): Contrast, Difference. The given status quo is ruled obsolete in principle and by definition, for good reason and by its own admission.

What, then, is the role and future of literate school (that is, contemporary education as such, across all levels) in electracy?

Change

We know in advance and in principle how the world works--that change happens in a certain way. It is even the case that there seems to be a hierarchy of being across all levels of existence, from atoms to galaxies, including the human dimension both biological and cultural. Any one level in this cosmology may function as a mise en abyme (miniaturization) for the organization of the whole (if one has the craft of allegory in mind). Here for example is an account of change in this holistic perspective, with reference to the atomic level.

Change begins slowly, uncertainly, and in places that are highly dependent upon local circumstances because the nuclei necessarily are misfits in the existing structure or orthodoxy. The nuclei are unpredictable (except perhaps by the Witch of Endor of whom Banquo demanded "If you can look into the seeds of time, and say which grains will grow and which will not, Speak then to me") because no system can by itself know ahead of time what, if any, new structure can supplant it. Nuclei do form, however, in those regions of the old structure that are least contented. A phase change is analogous to a political revolution; not the destruction of all individuals but the rearrangement of most of them into a new pattern of interaction. A revolution, driven by the injustices of the old regime, needs its formative nucleus, and its growth (which occurs in an interface of high disorder) is slowed by the need to accommodate or eliminate dissenters. Eventually, however, the structure that began as the highly creative work of a successful innovator becomes an ideology and as it spreads it becomes indoctrination, not creation. Cyril Stanley Smith, "Structural Hierarchy in Science, Art, and History," in On Aesthetics in Science, Ed. Judith Wechsler, MIT Press.

What remains for us to decide is not whether to participate in change, but the locus of our position in the array: with the normative lock, the gaps, or the misfits (the resistance, the opportunity, or the trouble)?

Rationale

Our collaboration begins with a review of the rationale for undertaking a more radical reform of education, rather than simply making a few adjustments to the status quo. The first reason ("Apparatus") is the historical analogy, associated with the simple reality of the migration of the archive accumulated during the 2500-year epoch of literacy due to information overload. Historically each apparatus first put its archive into a new medium of storage, and in the process invented a fundamentally different metaphysics (orientation to reality). School itself is a product of this invention within orality of the institution that created literacy. School is relative to the apparatus of literacy, and as such will continue within electracy, even adapting to digital technology, while having to accommodate the new dimension of civilization emerging within electracy. Part of the purpose of this Group is to articulate the nature of this new metaphysics, to determine the most appropriate and effective operation of school in this transforming reality. We speak from within the institution of school, looking back on the historical relationship of school with church and religion, and forward to the emerging relationship of school with corporation and entertainment.

Design and Electracy

In my case, I was schooled in two different architectural education traditions, both of which I came to interrogate as I pursued an interest in a range of crtical and theoretical writing, especially 1960s to 90s French criticism and philosophy. Of particular interest were accounts of technical change and its implications, including McLuhan's various books; but I appreciated the implicit critique offered by what I hold to be the more suggestive philosophy of Jacques Derrida in particular. I found Greg Ulmer's Applied Grammatology vivid in its linkage of Derridean theory with a range of cultural initiatives (Beuys' artwork, Lacan's psychoanalysis, Eisentein's film), and used the book as a template of sorts in my own creative design practice in Paris, dECOi Architects. At issue is the shift to a digital paradigm, and I found the speculative thinking useful in devising a range of architectural design practices that resulted in some quite original design work and some brief texts that framed or spurred the various initiatives. My interest, existing in a somewhat estranged and therefore experimental situation in Paris, was to think through a range of new principles for creative praxis in the plastic arts (and the arts in general); and this informed my teaching in a variety of European schools such as the AA in London. My sense is that architectural education has undergone a quite radical shift in the past few decades, to a large degree as a reaction to striking apparatus change; but the pribciples of this change have not been well formulated, even whilst being prescient. In coming to MIT I have witnessed a range of technical developments at first hand, but I feel that architectural design pedagogy in its most experimental drive, might offer lessons to other areas of education if it can be adequately theorized. My cogent interest in linking up with Greg Ulmer in the context of the recent Recommendations for the Future of MIT Education, is to bring my understanding of emerging digital design practice and its education within the historical framing of apparatus theory he offers, to see what might result. I also find it extremely useful to my teaching to be helped by such an erudite thinker who is patient and generous with his remarkable knowledge and (always) imaginative verve.