Choragraphy

To recover an original experience of Being recorded at the beginnings of literacy in Classical Greece, Heidegger turned to the Pre-Socratic philosophers such as Anaximander to find clues regarding Phusis prior to Idea and Concept. We are taking up Heidegger's promotion of this other beginning as a guide for the design of an electrate metaphysics. Heidegger acknowledges that his is still a method, hence is using literacy to bootstrap into this other "way" (and he means for us to hear an association with Asian Tao, as the family of his Event [Ereignis]--event replacing object in his new ontology). Literate conceptual thinking reduces everything to "calculation," whereas thinking event is like following a path, even what Heidegger calls "Holzwege" or forest paths, often overgrown, that come to an abrupt stop or dead end. The path may (or not) connect one location with another, not without errancy or wandering. The "forest" in Holzweg as a figure of method refers to any craft, such as the craft of poetry, and the "path" refers to the internal relationships and affordances of the material and practices that a craftsman learns and uses in making. What Heidegger wants to learn from poets is how to receive from language and the formal conventions of art direction for the creation of sense and significance. Calculation produced our superb contemporary GPS systems. The task of electracy is to supplement GPS with EPS--existential positioning system--capable of wayfinding relevant to Holzwege as electrate logic.

Heidegger's "path" repeats Anaximander's own move in the invention of Philosophy, which was to find an equivalent in the new apparatus of alphabetic writing for the craft-work of well-made objects (craft as Analogy). The decision that sent literacy on its way into Idea and Category is recorded in the drama of Socrates, who began his career as gadfly in the city when the Oracle at Delphi declared that no one was wiser than Socrates. Refusing to accept this assertion, Socrates set out to question craftsmen of every sort, experts in all the important specializations of the day, from shipbuilders to generals. As the dialogues demonstrate, he found that however seasoned in their craft, none of his interlocutors possessed wisdom (knowledge of universal principles, the true nature of reality). They lacked this kind of knowledge, of course, because it was only then being invented. Heidegger returns to the Pre-Socratics whose cosmology records precisely what he wants to understand--the emergence of Being, not the qualities of extant beings. Anaximander is himself a transitional figure (just as was Socrates after him), being also a craftsman. The "emergence" in question is that of order and its measure of beings (the elements) out of chaos, their ebb and flow, coming and going, upsurge and destruction, through time.

The truth that Anaximander expressed in his written text he also modeled with three inventions, three daidala, representations of cosmos relevant to the work or craft of theory (Theoria). Theoria involved travel, journeys both literal and figurative, undertaking investigation and speculation. In support of this work Anaximander designed the first celestial sphere, a map of the world, and a gnomon (as sundial to track time) (Indra Kagis McEwen, Socrates' Ancestor: An Essay on Architectural Beginnings, MIT, 1993: 17). Well-made crafts (an excellent ship or poem) had a double function: they physically gathered and arranged material into function and service, and through the beauty of the well-made object order showed itself and appeared. This production of cosmos through making applies to every dimension, not only objects but also moral ethos, the city as place and as political order (Justice). Adornment reveals nature, cosmetics show beauty of face, and revelation through craft is what Heidegger took as his point of departure for the other beginning leading to our digital metaphysics.

The legendary figure most associated with cosmological craft is Daedalus, who fled Athens (went into exile) to the court of King Minos in Crete. The emergence of order that models our instructions is expressed in this legend, whose terms are clarified by their usage in Homer's epics, especially the Odyssey (hence the connection with the cleverness of Odysseus/Ulysses). The ambiguity or double nature of emergence is documented in the daidala credited to Daedalus: both Labyrinth and Choros (dance floor). In craft, dead-end wandering transforms into dance, just as cosmos emerges from chaos. "Diodorus Siculus uses the same adjective, apeiros, to describe the tortuous dead-end passages of Daedalus' Labyrinth, for apeiros means not only boundless but also, like aporia, without escape, which is also to say unmeasured, or immeasurable. It is the measure of Ariadne's dance, the confused regularity of the 'moving maze' traced by the passage of 'well-taught feet,' which spins the thread that leads out of the Labyrinth, and goes on to weave another. In the still-living imagery of Minoan murals, slim Cretan youths leap over the horns of death-dealing bulls in order to dance with them. For the early Greeks, the dangers of aporia were not problems to be solved but the basic precondition for artifice" (59). We are reminded by this vocabulary of the novel Gradiva, that Freud adopted as allegory of psychoanalytic pedagogy, including the peculiar gait that identified the historical, mythological, and actual women for the protagonist. "The feet of the dancers in Ariadne's dance are epistamenoisi, knowing feet, and one cannot claim to have knowledge of dancing until one can, in fact, dance" (126). The fundamental difference between literate idea and the other beginning is this role of experience, the participation in the craft, as distinct from pure knowledge, of having seen what is already given. The separation of the virtues of capability into knowing, doing, and making, characteristic of literacy is reversed in theopraxesis: the dancer, dance, and dance floor that make cosmos appear.

Here is our question, what calls for thinking in electracy, a new opportunity, taking up in our turn in our apparatus the confrontation between human power (virtue, capacity) and Deinon, leaving techne to literacy. We understand that it is a certain kind of relation, a jointure to create order, limit, well-being against violent disaster in the breach opened by humankind. Literacy took the way of Idea and conceptual logic with which we are familiar, with extraordinary results certainly. And yet today Deinon reigns. Our assignment is to develop for and through post-medium arts a new operating logic, another way of dis/joining, different from the analogy of the line, the allegory of the cave, the ratio of proportion structuring Plato's metaphysics (and Western thought after him). It is important to note, in this context, that Heidegger's Open (Breach), the gap of dis/joining, explicitly refers to one of Plato's most important innoavations, offered in Timaeus (a companion dialogue with the Republic). Plato took up in turn the gap or joint broached in the Pre-Socratics. To solve the problem of how Being and Becoming (the Intelligible and the Sensible) interacted (how pure eternal forms somehow direct the changing transcience of matter), Plato introduced a third dimension that he called "chora," borrowing from ordinary Greek the term for region, space, receptacle, and evoking the legendary daidala such as choros (dance floor) and chorus (in tragedy).

In Timaeus there is a first attempt to account for cosmos (joining into relation) strictly through Intelligible Form (Idea), but the account breaks off and its inadequacy acknowledged. A second account begins, that introduces between Being and Becoming, on the cusp or threshold of passage between the two kinds (the location of hinge or joint), this event of inmixing, jointure, emergence: Chora. Since Chora is neither intelligible nor sensible, it may only be discussed in poetic allusive terms (muthos, the mythology that Plato had hoped to avoid). The Theory (Pythagoras) directing Plato's invention held that world order emerges from chaos, disorder, obscurity. Chora is how Plato includes the event of emergence in his metaphysics, and Heidegger's aletheia and jointure return to it, privilege it as an augmentation of the other beginning, neglected by the tradition. Choragraphy names the designing of relations, of jointure or ratio of what is fitting, appropriation. Scholars have demonstrated the interdependence of Idea and Receptacle throughout the Western tradition, with Kant's third critique assigning to imagination the functioning of Chora, bridge between Pure and Practical Reason, Necessity and Freedom. The larger implications of this genealogy become clear when we recognize the Unconsious as the most recent treatment of the primordial gap.

Share this

Comments

Fouring

An introduction to electrate learning involves participation in an event of the emergence of Being. We are prepared now to appreciate the value of Analogy provided by Sterbak and Brodsky, as instructions for theopraxesis. Brodsky fits well with the Theory relay from Anaximander/Heidegger, given his late poem "Daedalus in Sicily" (1993). "Here, in Sicily, stiff on its scorching sand,/ sits a very old man, capable of transporting/ himself through the air, if robbed of other means of passage./ All his life he was building something, inventing something./ All his life from those clear constructions, from those inventions,/ he had to flee. . . . Yet he had already invented, when he was young, the seesaw,/ using the strong resemblance between motion and stasis./ The old man bends down, ties to his brittle ankle/ (so as not to get lost) a lengthy thread,/ straightens up with a grunt, and heads out for Hades" (Collected Poems in English, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 2000: 404).

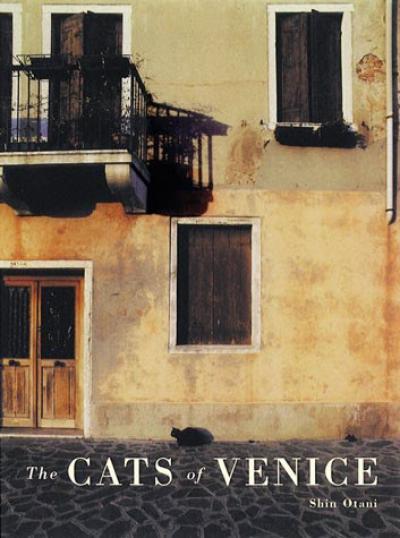

David MacFadyen noted "Daedalus in Sicily" as the signature text of late Brodsky (1990-96), in part because the organizing conceit of Watermark, the image used to express the feeling or experience of Venice for Brodsky, is that of the Daedalian Labyrinth. "The whole business is Daedalus' brain child, the labyrinth especially, as it resembles a brain. In a manner of speaking, everybody is related to everybody, the pursuer to the pursued, at least. Small wonder, then, that one's meanderings through the streets of this city, whose biggest colony for nearly three centuries was the island of Crete, feels somewhat tautological, especially as light fades--that is, especially as its pasiphaian, ariadnan, and phaedran properties fail. In other words, especially in the evening, when one loses oneself to self-deprecation" (Watermark, 87). MacFayden's reading superimposes the Daedalus poem on Watermark, identifying "nomadism" as the trope gathering "the maze of fifty-one prose vignettes" into formal coherence, felting into one digressive portrait events dispersed through nearly twenty years. "The metaphysical potential of Venice's dignity in decay is investigated a posteriori by Brodsky, so that he might later advocate it to others as a rule, a priori. Like Daedalus setting off towards an empirical investigation of death, with a thread trailing behind him in the hope that he might return from oblivion, the poet sets off into the labyrinthine streets of Venice, leaving a meandering narrative behind him of his findings, which urge their reader to overcome the danger of vanishing unnoticed into physical or metaphysical death. Watermark reflects this deliberate meandering or nomadism both in form, with its multiple vignettes and in content, with its tale of a maximally devolved poet going the final few steps, back into the muddy, alluvial source from which all life and language once sprang" (David MacFadyen, Joseph Brodsky and the Baroque, Ithaca: McGill-Queen's University Press: 1998: 175).

The basis for MacFadyen's classification of Brodsky as exemplary of a contemporary "neo-baroque" aesthetic is his use of the conceit in a style he learned from the English Metaphysical poet, John Donne, among others. The conceit yokes together the disparate, the unlike, known as discordia concors, hence its association with wit, considered as a mode of perception (K. K. Ruthven, The Conceit, London: Methuen, 1969). The conceit anticipates surrealist dissociation, disjuncture, which is the mode of jointure required for designing correspondences in electracy. Heidegger's poetics of the fourfold, das Geviert--his replacement for the proportional analogy structuring Plato's Line--extends the range of the conceit to gather microcosm-macrocosm relationships. He demonstrates the poetic manner of jointure precisely with reference to a potter's jug as "thing." His fouring distances itself also from the four-square of Aristotle's categories. Aristotle continued the decision of idea that forgot about emergence (presencing and withdrawal) to focus on beings as object. He accepted the inheritance of Pre-Socratic kosmoi, of craft as what makes order appear, and in fact adopts it as his own analogy to explain causality. In the case of a bronze statue, for example, the material cause is "that out of which" (the bronze); formal cause (the shape of the statue); efficient cause (the source of change: the artisan and the art of casting); final cause, that for the sake of which a thing is done, the purpose. Aristotle promotes fabrication to universal status as his creation story, achieving closure, Heidegger says, in our modern condition of capitalist commodities (product).

As an alternative to this metaphysics of Techne (of product and object), Heidegger places the jug within a narrative of event. It is a holistic regioning (chora) in which the nature of the jug in its capacity as vessel (receptacle), a void capable of holding, is revealed in the context of its ritual usage, the pouring of a libation of wine, a sacrifice to the divine. The jug as conceit fits the act of pouring out wine with the relation of gift between gods and mortals. "The gift of the outpouring is a gift because it stays earth and sky, divinities and mortals. Yet staying is now no longer the mere persisting of something that is here. Staying appropriates. It brings the four into the light of their mutual belonging. From out of staying's simple onefoldness they are betrothed, entrusted to one another. The gift of the outpouring stays the onefold of the fourfold of the four. And in the poured gift the jug presences as jug" (Heidegger, "The Thing," Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Albert Hofstadter, New York: Harper & Row, 1971: 173). This fouring is a poetics of theopraxesis that calls attention to the challenge of EPS for a digital apparatus. Heidegger discusses the question in terms of the transformation of what is meant by neighborhood now, the turning of what is near and far.

Popcycle

One's geographical location is just one dimension of four in an electrate cosmology, or five, if you count the emergence of Being resulting from their jointure. Brodsky's world demonstrates the fourfold as relay for our own EPS. We have extrapolated from these four-square systems our own relational ratio. Where is Joseph Brodsky, when he is in Venice, Italy? A neighborhood that we call the popcycle consists of at least four sites, four dimensions, whose intersection at the crossroads of chiasmus unites four into one. Mythology (popular culture): Brodsky fantasized "Venice" before he was exiled, before he ever thought it would be possible to go there, given the confinement of Russians in the Soviet era. The Venice he visited as soon as it became possible was the one of Visconti's film, Death in Venice. Memory (Family): In interviews Brodsky explained that part of the attraction of Venice was that it reminded him of his home town, St Petersburg (formerly Leningrad). His memory of home, recounted in anecdotes, included that of his father returning from one of his trips as a photojournalist for Soviet media with a gift of a toy, a souvenir copper gondola from Venice. This souvenir was still on the adult Brodsky's bookshelf, preserved in a memorial exhibit, reconstructed from a photograph of his room the day he suddenly departed for the West. History (Community): Brodsky was an exile by disposition long before he was exiled by the state. His acknowledgement of his historical community is found in an image he used to explain the experience of exile. The image draws upon the Soviet space program, the experiment of sending of dogs into space before risking human passengers. "To be an exiled writer is like being a dog or a man hurtled into outer space in a capsule (more like a dog, of course, than a man, because they will never bother to retrieve you). And your capsule is your language. To finish the metaphor off, it must be added that before long the passenger discovers that the capsule gravitates not earthward but outward in space" (Brodsky, "The Condition We Call Exile," in Altogether Elsewhere: Writers on Exile, Ed. Marc Robinson, New York: Harvest, 1994: 10). This historical metaphor continues into the dimension of Career (Craft), which is the anagogy of this allegorical ratio. Describing the style of the novelist Platonov (one cannot help but notice "Plato" in the name), Brodsky ties together the full conceit of his popcycle. "He [Platonov] will lead the sentence into some kind of logical dead-end. Always. Consequently, in order to comprehend what he is saying, you have to sort of 'back' from the dead-end and then to realize what brought you to that dead-end. And you realize that this is the grammar, the very grammar, of the Russian language itself," (Joseph Brodsky: Conversations, Ed. Cynthia L. Haven, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2002: 49). The Labyrinth repeats across all levels, producing nearing, a neighborhood.

The App of konsult that we are inventing for an electrate fifth estate maps one's existential neighborhood (choragraphy). Venice as scene is a palimpsest of dimensions: the meandering streets and canals recall those of St. Petersburg, but also the Labyrinth and Choros of Daedalus, and even the very grammar of the Russian language, all evoking finally the state of mind, the mood of the poet Joseph Brodsky. The city outside gives meaning to his state of being (Heidegger's attunement). His theme he said is what time does to a man. His formula is time equals water; time passing is recorded in the dilapidation of the architecture in Venetian buildings, which decay from the bottom up. He offers his own updating of the allegories we have collected. "I simply think that water is the image of time, and every New Year's Eve, in somewhat pagan fashion, I try to find myself near water, preferably near a sea or an ocean, to watch the emergence of a new helping, a new cupful of time from it. I am not looking for a naked maiden riding on a shell; I am looking for either a cloud or the crest of a wave hitting the shore at midnight. That, to me, is time coming out of water, and I stare at the lace-like pattern it puts on the shore, not with a gypsy-like knowing, but with tenderness and with gratitude" (Watermark, 43). Brodsky's neighborhood may be an emblem of Existential Positioning in general, considering that the concetto concentrating the experience of his disposition is some small vessel--chora, receptacle--the gondola souvenir, the space capsule, even the room-and-a-half in which his family lived in St Petersburg, where he created for himself a little cubicle, walling himself off from his parents with his bookshelf. These are figures of travel at the same time, referencing his particular power of poetic imagination, his craft. Each of us may ask: what is that for me, in my own case? What belongs to me? What is my own neighborhood? Here is our assignment, the project for the invention of electrate metaphysics.